Dandy

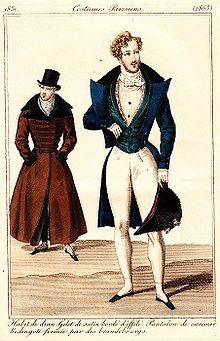

A dandy is a man who places particular importance upon physical appearance and personal grooming, refined language and leisurely hobbies. A dandy could be a self-made man both in person and persona, who emulated the aristocratic style of life regardless of his middle-class origin, birth, and background, especially during the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Britain.[1][2][3]

Early manifestations of dandyism were Le petit-maître (the Little Master) and the musk-wearing Muscadin ruffians of the middle-class Thermidorean reaction (1794–1795). Modern dandyism, however, emerged in stratified societies of Europe during the 1790s revolution periods, especially in London and Paris.[4] Within social settings, the dandy cultivated a persona characterized by extreme posed cynicism, or "intellectual dandyism" as defined by Victorian novelist George Meredith; whereas Thomas Carlyle, in his novel Sartor Resartus (1831), dismissed the dandy as "a clothes-wearing man"; Honoré de Balzac's La fille aux yeux d'or (1835) chronicled the idle life of Henri de Marsay, a model French dandy whose downfall stemmed from his obsessive Romanticism in the pursuit of love, which led him to yield to sexual passion and murderous jealousy.

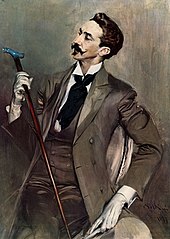

In the metaphysical phase of dandyism, the poet Charles Baudelaire portrayed the dandy as an existential reproach to the conformity of contemporary middle-class men, cultivating the idea of beauty and aesthetics akin to a living religion. The dandy lifestyle, in certain respects, "comes close to spirituality and to stoicism" as an approach to living daily life,[5] while its followers "have no other status, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons, of satisfying their passions, of feeling and thinking … [because] Dandyism is a form of Romanticism. Contrary to what many thoughtless people seem to believe, dandyism is not even an excessive delight in clothes and material elegance. For the perfect dandy, these [material] things are no more than the symbol of the aristocratic superiority of mind."[6]

The linkage of clothing and political protest was a particularly English characteristic in 18th-century Britain;[7] the sociologic connotation was that dandyism embodied a reactionary form of protest against social equality and the leveling effects of egalitarian principles. Thus, the dandy represented a nostalgic yearning for feudal values and the ideals of the perfect gentleman as well as the autonomous aristocrat – referring to men of self-made person and persona. The social existence of the dandy, paradoxically, required the gaze of spectators, an audience, and readers who consumed their "successfully marketed lives" in the public sphere. Figures such as playwright Oscar Wilde and poet Lord Byron personified the dual social roles of the dandy: the dandy-as-writer, and the dandy-as-persona; each role a source of gossip and scandal, confining each man to the realm of entertaining high society.[8]

Etymology

[edit]The earliest record of the word dandy dates back to the late 1700s, in Scottish Song [1]. Since the late 18th century, the word dandy has been rumored to be an abbreviated usage of the 17th-century British jack-a-dandy used to described a conceited man.[9] In British North America, prior to American Revolution (1765–1791), a British version of the song "Yankee Doodle" in its first verse: "Yankee Doodle went to town, / Upon a little pony; / He stuck a feather in his hat, / And called it Macoroni … ." and chorus: "Yankee Doodle, keep it up, / Yankee Doodle Dandy, / Mind the music and the step, / And with the girls be handy … ." derided the rustic manner and perceived poverty of colonial American. The lyrics, particularly the reference to "stuck a feather in his hat" and "called it Macoroni," suggested that adorning fashionable attire (a fine horse and gold-braided clothing) was what set the dandy apart from colonial society.[10] In other cultural contexts, an Anglo–Scottish border ballad dated around 1780 utilized dandy in its Scottish connotation and not the derisive British usage populated in colonial North America.[11] Since the 18th century, contemporary British usage has drawn a distinction between a dandy and a fop, with the former characterized by a more restrained and refined wardrobe compared to the flamboyant and ostentatious attire of the latter.[12]

British dandyism

[edit]

The illustration, by E. J. Sullivan, is from an 1898 edition of the novel Sartor Resartus (1831), by Thomas Carlyle.

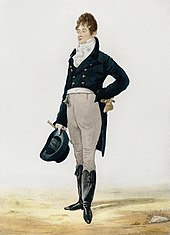

Beau Brummell (George Bryan Brummell, 1778–1840) was the model British dandy since his days as an undergraduate at Oriel College, Oxford, and later as an associate of the Prince Regent (George IV) – all despite not being an aristocrat. Always bathed and shaved, always powdered and perfumed, always groomed and immaculately dressed in a dark-blue coat of plain style.[13] Sartorially, the look of Brummell's tailoring was perfectly fitted, clean, and displayed much linen; an elaborately knotted cravat completed the aesthetics of Brummell's suite of clothes. During the mid-1790s, the handsome Beau Brummell became a personable man-about-town in Regency London's high society, who was famous for being famous and celebrated "based on nothing at all" but personal charm and social connections.[14][15]

During the national politics of the Regency era (1795–1837), by the time that Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger had introduced the Duty on Hair Powder Act 1795 in order to fund the Britain's war efforts against France and discouraged the use of foodstuffs as hair powder, the dandy Brummell already had abandoned wearing a powdered wig and wore his hair cut à la Brutus, in the Roman fashion. Moreover, Brummell also led the sartorial transition from breeches to tailored pantaloons, which eventually evolved into modern trousers.

Upon coming of age in 1799, Brummell received a paternal inheritance of thirty thousand pounds sterling, which he squandered on a high life of gambling, lavish tailors, and visits to brothels. Eventually declaring bankruptcy in 1816, Brummell fled England to France, where he lived in destitution and pursued by creditors; in 1840, at the age of sixty-one years, Beau Brummell passed away in a lunatic asylum in Caen, marking the tragic end to his once-glamorous legacy.[16] Nonetheless, despite his ignominious end, Brummell's influence on European fashion endured, with men across the continent seeking to emulate his dandyism. Among them was the poetical persona of Lord Byron (George Gordon Byron, 1788–1824), who wore a poet's shirt featuring a lace-collar, a lace-placket, and lace-cuffs in a portrait of himself in Albanian national costume in 1813;[17] Count d'Orsay (Alfred Guillaume Gabriel Grimod d'Orsay, 1801–1852), himself a prominent figure in upper-class social circles and an acquaintance of Lord Byron, likewise embodied the spirit of dandyism within elite British society.

In chapter "The Dandiacal Body" of the novel Sartor Resartus (Carlyle, 1831), Thomas Carlyle described the dandy's symbolic social function as a man and a persona of refined masculinity:

A Dandy is a Clothes-wearing Man, a Man whose trade, office, and existence consists in the wearing of Clothes. Every faculty of his soul, spirit, purse, and person is heroically consecrated to this one object, the wearing of Clothes wisely and well: so that as others dress to live, he lives to dress. . . .

And now, for all this perennial Martyrdom, and Poesy, and even Prophecy, what is it that the Dandy asks in return? Solely, we may say, that you would recognise his existence; would admit him to be a living object; or even failing this, a visual object, or thing that will reflect rays of light.[18]

In the mid-19th century, amidst the restricted palette of muted colors for men's clothing, the English dandy dedicated meticulous attention to the finer details of sartorial refinement (design, cut, and style), including: "The quality of the fine woollen cloth, the slope of a pocket flap or coat revers, exactly the right colour for the gloves, the correct amount of shine on boots and shoes, and so on. It was an image of a well-dressed man who, while taking infinite pains about his appearance, affected indifference to it. This refined dandyism continued to be regarded as an essential strand of male Englishness."[19]

French dandyism

[edit]

In monarchic France, dandyism was ideologically bound to the egalitarian politics of the French Revolution (1789–1799); thus the dandyism of the jeunesse dorée (the Gilded Youth) was their political statement of aristocratic style in effort to differentiate and distinguish themselves from the working-class sans-culottes, from the poor men who owned no stylish knee-breeches made of silk.

In the late 18th century, British and French men abided Beau Brummell's dictates about fashion and etiquette, especially the French bohemians who closely imitated Brummell's habits of dress, manner, and style. In that time of political progress, French dandies were celebrated as social revolutionaries who were self-created men possessed of a consciously designed personality, men whose way of being broke with inflexible tradition that limited the social progress of greater French society; thus, with their elaborate dress and decadent styles of life, the French dandies conveyed their moral superiority to and political contempt for the conformist bourgeoisie.[20]

Regarding the social function of the dandy in a stratified society, like the British writer Carlyle, in Sartor Resartus, the French poet Baudelaire said that dandies have "no profession other than elegance … no other [social] status, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons. … The dandy must aspire to be sublime without interruption; he must live and sleep before a mirror." Likewise, French intellectuals investigated the sociology of the dandies (flâneurs) who strolled Parisian boulevards; in the essay "On Dandyism and George Brummell" (1845) Jules Amédée Barbey d'Aurevilly analysed the personal and social career of Beau Brummell as a man-about-town who arbitrated what was fashionable and what was unfashionable in polite society.[21]

In the late 19th century, dandified bohemianism was characteristic of the artists who were the Symbolist movement in French poetry and literature, wherein the "Truth of Art" included the artist to the work of art.[22]

Black dandyism

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

Black dandies have existed since the beginnings of dandyism and have been formative for its aesthetics in many ways. Maria Weilandt in "The Black Dandy and Neo-Victorianism: Re-fashioning a Stereotype" (2021) critiques the history of Western European dandyism as primarily centered around white individuals and the homogenization whiteness as the figurehead of the movement. It is important to acknowledge Black dandyism as distinct and a highly political effort at challenging stereotypes of race, class, gender, and nationality.

British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare (b. 1962) employs the neo-Victorian dandy stereotypes to illustrate the Black man experiences in Western European societies. Shonibare's photographic suite Dorian Gray (2001) refers to Oscar Wilde's literary creation of the same name,The Picture Of Dorian Gray (1890), but with the substitution of a disfigured Black protagonist. As the series progress, readers soon notice that there exists no real picture of "Dorian Gray" but only illustrations of other white protagonists. It is through this theme of isolation and Otherness that the Black Dorian Gray becomes Shonibare's comment on the absence of Black representation in Victorian Britain.

Shonibare's artwork Diary of a Victorian Dandy (1998) reimagines one day in the life of a dandy in Victorian England, through which the author challenges conventional Victorian depictions of race, class, and British identity by depicting the Victorian dandy as Black, surrounded by white servants.

By reversing concepts of the Victorian master-servant relationship, by rewriting stereotypings of the Victorian dandy to include Black masculinities, and by positioning his dandy figure as a noble man who is the leader of his social circle, Shonibare uses neo-Victorianism as a genre to interrogate and counter normative historical narratives and the power hierarchies they produce(d).[23]

Black dandyism serves as a catalyst for contemporary Black identities to explore self-fashioning and expressions of neo-Victorian Blacks: The Black dandy's look is highly tailored – the antithesis of baggy wear. [...] Black dandyism rejects this. In fact, the Black dandy is often making a concerted effort to juxtapose himself against racist stereotyping seen in mass media and popular culture [...] For dandies, dress becomes a strategy for negotiating the complexities of Black male identity [...].[24]

"Dandy Jim of Carolina" is a minstrel song that originated in the United States during the 19th century. It tells the story of a character named Dandy Jim, who is depicted as a stylish and flamboyant individual from the state of Carolina. The song often highlights Dandy Jim's extravagant clothing, his charm, and his prowess with the ladies. While the song does not explicitly address race, Dandy Jim's stylish and flamboyant persona aligns with aspects of Black dandyism, a cultural phenomenon characterized by sharp dressing, self-assurance, and individuality within Black communities.

According to the standards of the day, it was ludicrous and hilarious to see a person of perceived lower social standing donning fashionable attire and "putting on airs." For most of racist 19th century America a well dressed African American was an odd thing, and naturally someone of that ilk would be seen as acting out of place. The representation of Dandy Jim, while potentially rooted in caricature or exaggeration, nonetheless contribute to the broader cultural landscape surrounding Black dandyism and its portrayal in American folk music.

Dandy sociology

[edit]

Regarding the existence and the political and cultural functions of the dandy in a society, in the essay L'Homme révolté (1951), Albert Camus said that:

The dandy creates his own unity by aesthetic means. But it is an aesthetic of negation. To live and die before a mirror: that, according to Baudelaire, was the dandy's slogan. It is indeed a coherent slogan. The dandy is, by occupation, always in opposition [to society]. He can only exist by defiance … The dandy, therefore, is always compelled to astonish. Singularity is his vocation, excess his way to perfection. Perpetually incomplete, always on the fringe of things, he compels others to create him, while denying their values. He plays at life because he is unable to live [life].[25]

Further addressing that vein of male narcissism, in the book Simulacra and Simulation (1981), Jean Baudrillard said that dandyism is "an aesthetic form of nihilism" that is centred upon the Self as the centre of the world.[26]

Elizabeth Amann's Dandyism in the Age of Revolution: The Art of the Cut (2015) quotes, "Dandyism has always been a cross-cultural phenomenon".[27] Male self-fashioning carries socio-political implications beyond its superficiality and opulent external. Through the analysis of clothing, aesthetics, and societal norms, Amann examines how dandyism emerged as a means of asserting identity, power, and autonomy in the midst of revolutionary change. Male self-fashioning, in particular, was wielded as a resistance expression in denial of itself due to the influence of the French Revolution on British discussions of masculinity. British prime minister William Pitt proposed an unusual measure: the Duty on Hair Powder Act 1795, which aimed to levy a tax on from affluent consumers of hair powder to raise money for the war. Critics of the act expressed fear regarding the association between wearing hair powder and "a tendency to produce a famine,” and those who did so would “run the further risque of being knocked on the head”.[28] In August 1975, journalists and new reports complained that "the papers had misled the poor and encouraged them to consider powdered heads their enemies," a “calculated to excite riots.” [29] With the new legislation, the powdered look became a marker of class in English society and a much more exclusive one, polarizing those who used the products and those who did not. Those who feared making class boundaries too visible considered the distinctions to be deep and significant and therefore wished to protect them by making them less evident, by allowing a self-fashioning that created an illusion of mobility in a highly stratified society.

In the early discussion of the tax, the London Packet posed the question, “Is an actor, who in his own private character uniformly appears in a scratch wig, or wears his hair without powder, liable to pay the tax imposed by the new act, for any of the parts which he is necessitated to dress with powder on the stage?” This seemingly trivial inquiry unveils a profound aspect of the legislation: By paying the tax, citizens were essentially purchasing the right to craft a persona, akin to an actor who took on a stage role. Exaggerated self-fashioning was no longer an oppositional strategy and instead became the prevailing norm. To protest the tax and the war against France was to embrace a new aesthetic of invisibility, wherein individuals favored natural attire and simplicity in order to blend into the social fabric rather than stand out.

Dandyism and capitalism

[edit]Dandyism is intricately linked with modern capitalism, embodying both a product of and a critique against it. According to Elisa Glick, the dandy's attention to their appearance and their engagement "consumption and display of luxury goods" can be read as an expression of capitalist commodification.[30] However, interestingly, this meticulous attention to personal appearance can also be seen as an assertion of individuality and thus a revolt against capitalism's emphasis on mass production and utilitarianism.

Underscoring this somewhat paradoxical nature, philosopher Thorsten Botz-Bornstein describes the dandy as "an anarchist who does not claim anarchy."[31] He argues that this simultaneous abiding by and also ignorance of capitalist social pressures speaks to what he calls a “playful attitude towards life’s conventions." Not only does the dandy play with traditional conceptions of gender, but also with the socioeconomic norms of the society they inhabit; he agrees the importance that dandyism places on uniquely personal style directly opposes capitalism's call for conformity.

Thomas Spence Smith highlights the function of style in maintaining social boundaries and individual status, particularly as traditional social structures have decrystallized in modernity. He notes that "style becomes a crucial element in maintaining social boundaries and individual status."[32] This process "creates a market for new social models, with the dandy as a prime example of how individuals navigate and resist the pressures of a capitalist society." Here, another paradoxical relation between dandyism and capitalism emerges: dandyism's emphasis on individuality and on forming an idiomatic sense of style can be read as a sort of marketing or commodification of the self.

Quaintrelle

[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2008) |

The counterpart to the dandy is the quaintrelle, a woman whose life is dedicated to the passionate expression of personal charm and style, to enjoying leisurely pastimes, and the dedicated cultivation of the pleasures of life.

In the 12th century, cointerrels (male) and cointrelles (female) emerged, based upon coint,[33] a word applied to things skillfully made, later indicating a person of beautiful dress and refined speech.[34] By the 18th century, coint became quaint,[35] indicating elegant speech and beauty. Middle English dictionaries note quaintrelle as a beautifully dressed woman (or overly dressed), but do not include the favorable personality elements of grace and charm. The notion of a quaintrelle sharing the major philosophical components of refinement with dandies is a modern development that returns quaintrelles to their historic roots.

Female dandies did overlap with male dandies for a brief period during the early 19th century when dandy had a derisive definition of "fop" or "over-the-top fellow"; the female equivalents were dandyess or dandizette.[34] Charles Dickens, in All the Year Around (1869) comments, "The dandies and dandizettes of 1819–20 must have been a strange race. "Dandizette" was a term applied to the feminine devotees to dress, and their absurdities were fully equal to those of the dandies."[36] In 1819, Charms of Dandyism, in three volumes, was published by Olivia Moreland, Chief of the Female Dandies; most likely one of many pseudonyms used by Thomas Ashe. Olivia Moreland may have existed, as Ashe did write several novels about living persons. Throughout the novel, dandyism is associated with "living in style". Later, as the word dandy evolved to denote refinement, it became applied solely to men. Popular Culture and Performance in the Victorian City (2003) notes this evolution in the latter 19th century: " … or dandizette, although the term was increasingly reserved for men."

See also

[edit]- Adonis

- Bishōnen

- Dandy and Dedicated Follower of Fashion, songs by the Kinks that parody modern (1960s) dandyism.

- Dude

- Effeminacy

- Flâneur

- Fop

- Gentleman

- Hipster (contemporary subculture)

- Incroyables and Merveilleuses

- La Sape

- Macaroni (fashion)

- Metrosexual

- Narcissus (mythology)

- Personal branding

- Preppy

- Risqué

- Swenkas

- Zoot suit (a style of clothing)

References

[edit]- ^ a b dandy: "One who studies ostentatiously to dress fashionably and elegantly; a fop, an exquisite." (OED).

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1989. Archived from the original on 25 June 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

dude, n. U.S.A name given in ridicule to a man affecting an exaggerated fastidiousness in dress, speech, and deportment, and very particular about what is aesthetically 'good form'; hence extended to an exquisite, a dandy, 'a swell'.

- ^ Cult de soi-même, Charles Baudelaire, "Le Dandy", noted in Susann Schmid, "Byron and Wilde: The Dandy in the Public Sphere" in Julie Hibbard et al. , eds. The Importance of Reinventing Oscar: Versions of Wilde During the Last 100 Years 2002

- ^ Le Dandysme en France (1817–1839) Geneva and Paris, 1957.

- ^ Prevost 1957.

- ^ Baudelaire, Charles. "The Painter in Modern Life", essay about Constantin Guys.

- ^ Ribeiro, Aileen. "On Englishness in Dress", essay in The Englishness of English Dress. Christopher Breward, Becky Conekin, and Caroline Cox, Eds., 2002.

- ^ Schmid 2002.

- ^ "jack-a-dandy", The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993) Lesley Brown, Ed. p. 1,434.

- ^ "Yankee Doodle"

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1989. Archived from the original on 25 June 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

Dandy 1.a. "One who studies, above everything, to dress elegantly and fashionably; a beau, a fop, an exquisite. A 1780 Scots song says: "I've heard my granny crack O' sixty twa' years back. When there were sic a stock of Dandies O; Oh they gaed to Kirk and Fair, Wi' their ribbons round their hair, And their stumpie drugget coats, quite the Dandy O.

See: Notes and Queries 8th Ser. IV. 81. - ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911, p. 0000.

- ^ "In Regency England, Brummel's fashionable simplicity constituted, in fact, a criticism of the exuberant French fashions of the eighteenth century" (Schmid 2002:83)

- ^ D'Aurevilly, Barbey. "Du dandisme et de George Brummell" (1845) in Oeuvres complètes (1925) pp. 87–92.

- ^ Kelly, Ian (2006). Beau Brummell: The Ultimate Man of Style. New York: Free Press. ISBN 9780743270892.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 6018–6019). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "Portrait of Lord Byron in Albanian Dress, 1813". The British Library. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas. "The Dandiacal Body", in Sartor Resartus (1833–1834).

- ^ Ribeira 2002:21.

- ^ Meinhold, Roman. "The Ideal-Typical Incarnation of Fashion: The Dandy as … ." essay in Fashion Myths: A Cultural Critique. Bielefeld, Germany: transcript, 2014. pp. 111–125. books.google.com/books?id=1XWiBQAAQBAJ ISBN 9783839424377

- ^ Walden, George. Who's a Dandy? – Dandyism and Beau Brummell, Gibson Square, London, 2002. ISBN 1903933188. Reviewed in Uncommon People, The Guardian, 12 October 2006.

- ^ Meinhold, Roman. "The Ideal-Typical Incarnation of Fashion: The Dandy as … ", essay in Fashion Myths: A Cultural Critique. Bielefeld, Germany: transcript, 2014. pp. 111–125. books.google.com/books?id=1XWiBQAAQBAJ ISBN 9783839424377

- ^ Weilandt, Maria (2022). Espinoza Garrido, Felipe; Tronicke, Marlena; Wacker, Julian (eds.). Black neo-Victoriana. Neo-victorian series. Leiden ; Boston: Brill. pp. 189–209. ISBN 978-90-04-46914-3.

- ^ Byrd, Rikki (2 April 2018). "Rikki Byrd. Review of "Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style" by Shantrelle P. Lewis". Caa.reviews. doi:10.3202/caa.reviews.2018.100. ISSN 1543-950X.

- ^ Camus, Albert (2012). "II Metaphysical Rebellion". The Rebel: An Essay on Man in Revolt. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 51. ISBN 9780307827838. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ "Simulacra and Simulations – XVIII: On Nihilism". Egs.edu. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ Amann, Elizabeth (2015). Dandyism in the age of Revolution: the art of the cut. Chicago London: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-18725-9.

- ^ Ditchfield, G. M.; Hayton, David; Jones, Clyve (October 1994). "British Parliamentary Lists, 1660–1800: A Register". Parliamentary History. 13 (3): 388. doi:10.1111/j.1750-0206.1994.tb00312.x. ISSN 0264-2824.

- ^ "St James's Hall", Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001, doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.24320, retrieved 13 May 2024

- ^ Glick, Elisa (2001). "The Dialectics of Dandyism". Cultural Critique. 48 (48): 129–163. doi:10.1353/cul.2001.0035. ISSN 0882-4371. JSTOR 1354399.

- ^ Botz-Bornstein, Thorsten (1995). "Rule-Following in Dandyism: 'Style' as an Overcoming of 'Rule' and 'Structure'". The Modern Language Review. 90 (2): 285–295. doi:10.2307/3734540. ISSN 0026-7937. JSTOR 3734540.

- ^ Smith, Thomas Spence (1974). "Aestheticism and Social Structure: Style and Social Network in the Dandy Life". American Sociological Review. 39 (5): 725–743. doi:10.2307/2094317. ISSN 0003-1224. JSTOR 2094317.

- ^ Old English Dictionary

- ^ a b Brooks, Ann (2014). Popular Culture: Global Intercultural Perspectives. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 9781137426727.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Dictionary of Early English

- ^ All the Year Round: A Weekly Journal. Chapman & Hall. 1869.

Further reading

[edit]- Barbey d'Aurevilly, Jules. Of Dandyism and of George Brummell. Translated by Douglas Ainslie. New York: PAJ Publications, 1988.

- Botz-Bornstein, Thorsten. 'Rulefollowing in Dandyism: Style as an Overcoming of Rule and Structure' in The Modern Language Review 90, April 1995, pp. 285–295.

- Carassus, Émile. Le Mythe du Dandy 1971.

- Carlyle, Thomas. Sartor Resartus. In A Carlyle Reader: Selections from the Writings of Thomas Carlyle. Edited by G.B. Tennyson. London: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

- Jesse, Captain William. The Life of Beau Brummell. London: The Navarre Society Limited, 1927.

- Lytton, Edward Bulwer, Lord Lytton. Pelham or the Adventures of a Gentleman. Edited by Jerome McGann. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1972.

- Moers, Ellen. The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm. London: Secker and Warburg, 1960.

- Murray, Venetia. An Elegant Madness: High Society in Regency England. New York: Viking, 1998.

- Nicolay, Claire. Origins and Reception of Regency Dandyism: Brummell to Baudelaire. PhD diss., Loyola U of Chicago, 1998.

- Prevost, John C., Le Dandysme en France (1817–1839) (Geneva and Paris) 1957.

- Nigel Rodgers The Dandy: Peacock or Enigma? (London) 2012

- Stanton, Domna. The Aristocrat as Art 1980.

- Wharton, Grace and Philip. Wits and Beaux of Society. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1861.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). 1911.

- La Loge d'Apollon

- "Bohemianism and Counter-Culture": The Dandy Archived 22 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Il Dandy (in Italian)

- Dandyism.net

- "The Dandy"

- Walter Thornbury, Dandysme.eu "London Parks: IV. Hyde Park" Archived 1 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Belgravia: A London Magazine 1868